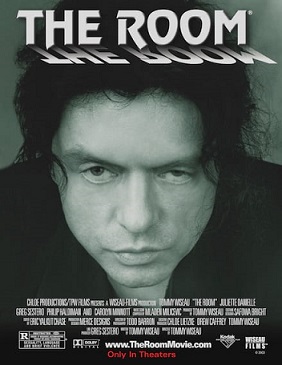

Like many people who attended liberal arts school in the mid 2010s, Tommy Wiseau’s The Room (2003) is embarrassingly integral to the emotional arc of my life. In summer of 2013, accepted students day at my first college was marked by a new friend explaining the mythos of the film in detail, and showing me The House That Dripped Blood on Alex– a Wiseau- Adult Swim coproduction. The first time I saw the movie in its entirety was that fall, with my first serious boyfriend. The occasion marked the beginning of a mutual hobby of consuming any so-bad-it’s-good media we could get our hands on. And, obviously, quoting Wiseau’s lines tirelessly in a mock accent (So how’s your sex life?). Two years later, when I had transferred schools and was in a deep depression, reading Greg Sestero’s- Tommy Wiseau’s close friend and costar’s- The Disaster Artist brought me genuine escape and nostalgic joy.

It wasn’t until a few weeks ago, though, crossfaded as hell and enjoying a yearly viewing, that I found myself wondering- What happens when we talk about The Room as a piece of art on it’s own merits? As a film qua film if we want to get real pretentious with it.

So much of The Room’s cultural presence and notoriety stem from the mythology that’s been built around it. It’s impossible to have a casual conversation about the film without veering into discussing it’s troubled production, or Wiseau himself- it’s deeply weird auteur. I feel everyone collectively got so lost in trying to rationalize and explain the Room’s absolutely bizarre execution that very few people have analyzed it as a standalone piece of media. When asked for input on what exactly the plot or message of the movie was, my roommate responded with “I couldn’t tell you, but I know Tommy Wiseau really doesn’t like women.” I honestly feel that’s a great assessment and starting point.

At face value, The Room is the story of Johnny, an All-American (lol) man who works at a bank in an unspecified position. He lives an idyllic life in San Francisco with his Fiancee Lisa, and appears to be loved by absolutely everyone (even the floral shop lady calls him her favorite customer). He maintains close friendships with many people in his apartment building, to the extent that they wander in and out of his home as they please. He’s also excessively kind and good natured, showering Lisa with affection and gifts, and going so far as to pay rent for Denny- an orphaned young man whom is practically his adopted son.

However, after Johnny fails to receive an expected promotion, Lisa decides that she no longer loves him or wishes to get married, against her mother’s urging. She instead decides she is in love with Mark- Johnny’s closest friend- and presses him into a sexual relationship, erstwhile luring the sober Johnny into drinking so that she can claim he became belligerent and assaulted her. As Lisa and Mark’s relationship escalates (despite Mark’s weak assertions that he doesn’t wish to hurt his best friend), Johnny grapples with the stress of being falsely accused of abuse. This comes to a head at Johnny and Lisa’s engagement party, where the revelation of the affair drives Johnny to commit suicide. Mark, Lisa, and Denny then weep over his body. Johnny is a wonderful man with a perfect life, destroyed by the opaque and nefarious whims of his female partner. End Scene.

As strange as it may sound coming from that plot description, I believe there is solid ground for a queer reading of The Room. This is not an argument for for reading of homoerotic subtext between the characters of Johnny and Mark, something suggested by the 2019 film adaption of Greg Sestero’s the Disaster Artist. The conflict therein frames Wiseau’s screenplay as a method of conveying to Sestero his hurt at having a woman (Sestero’s then-girlfriend) come between them. I’ve also been reminded by a friend that in the book itself, Sestero speculates that Wiseau is gay. I believe that reading sexual attraction into these characters’ relationship would thus imply conjecture about Wiseau (which is not my job here), and would also be groundless and politically vacuous. As Leo Bersani states in his essay Gay Betrayals:

“…gay literary studies, for example, is tireless in it’s pursuit of what is called homoeroticism in a significant number of significant writers from the past. We end up with the implicit but no less extraordinary proposition that gays aren’t homosexual but all straights are homoerotic… it seems to me little more than a provokingly tendentious way of asserting a certain sexual indeterminacy in all human beings, a state of affairs hardly discovered by queer studies.”

That is, stretching to find hints of queerness existent in texts which are explicitly heterosexual, and labeling that as homoerotic does little but assert the fluidity of the human sexual experience (which, duh), and helps brush over textuality which is explicitly homosexual. A hot take, but one I’m privy to. The male characters of The Room have hardly a sexually charged gaze shared between them. What there is, however, is a utopic sphere of male friendship- especially between Johnny and Mark, but extending to the entire friend group. I wish to argue instead for a queer masculinist reading of the film, which centers romantic(ized) male homosociality threatened by female sexual power.